Here’s the link to The Boston Globe version: That time I was headed nowhere, fast: A sci-fi novel delivered a message I couldn’t ignore. There could not have been a more apt metaphor for my cramped, small, myth-laden life.

Note: The much shorter, professionally edited version is a better essay that carries all the meaning of the longer version published here. However, there was a lot of background research that surfaces in this longer version. So, I think of this version as complimentary.

Mark gave me the first book I ever read, 43 years ago when I was a senior in high school. It was a science fiction novel meant for younger readers, but it inspired in me an exploration of words and books that took me to a college degree, a master’s and decades as a journalist.

Much of Mark’s identity and the circumstances of our conversation the day he gave me that novel have been lost to me, but I do remember being drawn to his challenging, knowledgeable and questioning attitude towards our social studies teacher.

After decades of remembering Mark and this era of my life, I sometimes get the feeling that telling someone “Think your own thoughts, but make sure they are your own thoughts” can be the most radical thing you can tell a person. I also understand that the phrase “Just let boys be boys” will get a lot of push back. But I was a boy, a long time ago, and have a story to tell about it that can’t easily be logged as being in any one political camp.

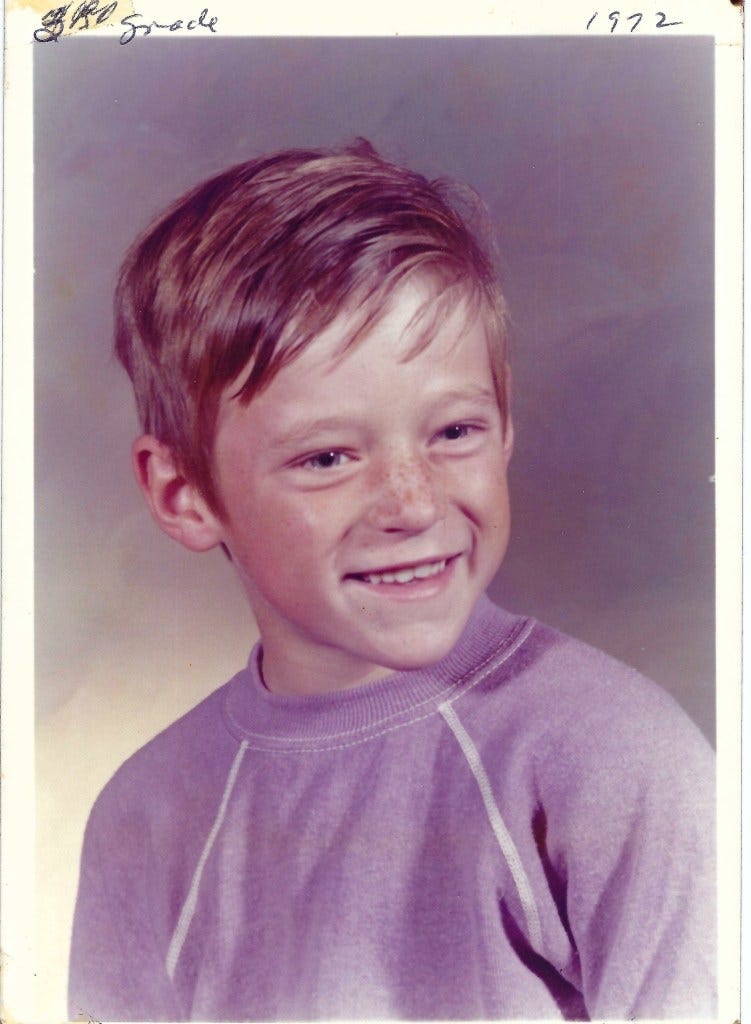

Prior to my senior year of 1981-’82, I had a grade point average in the low D range, poor attendance, lunch-time drinking and occasional pot smoking, pervasive classroom discipline problems, including fights in and out of class. In short, I was on a clear trajectory toward dropping out and joining the roughly 15 percent of male students in the early 1980s who didn’t finish high school.

Some might have thought I would end up in jail or prison, which would not have made me unique in my peer group. Between 1980 to 1982, mass incarceration really took off in America. That surge, largely due to the war on drugs and arrests for marijuana possession, hit communities of color much harder than white communities. However, between 1974 and 1991, the number of American white males like myself who had ever been incarcerated jumped from 837,000 to 1,395,000.

So, like millions of American boys and young men, past and present, I was well on my way to becoming a member of a working-class demographic statistically marching toward disaffection, emotional passivity, drug and alcohol abuse, suicidal tendencies, frequent violent encounters and stagnant wages.

The 1980’s economic scene

While the issue of boys and young men falling behind is getting more attention now, by 1982, the year I graduated, Americans were emerging from the worst economic recession since the Great Depression. Inflation was nearly 15 percent, and unemployment hovered around 11 percent. Male college attendance had already flattened, with women fast on the rise.

When the recession lifted, “three-fourths of the increase (in employment) was in services and retail trade, while manufacturing and mining lost workers,” states a 1990 report by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Traditionally male-dominated economic sectors that didn’t require education past high school took a hard hit and never really recovered. When those industries did increase production later in the 1980s, they did so through improved technology and far fewer workers, the report found.

Conversely, careers that benefit from higher education, particularly those in the“service sector” where no physical goods are produced, emerged as the dominant economic force. This sector encompasses fields such as medical and aging care, sales, financial services, information technology as well as technological and scientific research. These professions, often referred to as “white-collar,” typically require education beyond high school.

The 1980s also marked the beginning of significant social changes that some say are contributing to the trouble with males today: the rise of the independent woman who works outside of the home and has more of control over their reproductive lives and the erosion of the traditional male role in the economy and marriage. Divorces rates peaked in 1980, according to one univeristy study, while marriage rates among the less educated have continued to fall.

“The long economic expansion during the 1980s was reflected in strong employment growth in retail trade. Changing lifestyles, such as the increase in the percentage of women who work outside the home and in that of workers who have two jobs, also contributed to growth,” the 1990 bureau study states.

Those socio-economic changes triggered a tsunami of effects that run throughout the economy and our social lives today. Stores that sold timesaving devices and “offered service and convenience” as well as fast food were “among the most successful retail establishments of the 1980s,” the study explains.

“Eating and drinking places of all types headed the list of industries that added the most jobs in the 1980s,” it said. And by 1984, female employees at fast food establishments outnumbered males by two to one, according to research sponsored by the Department of Education.

The ‘rise of women’ didn’t limit men: Us men limited ourselves

The rise of women’s participation in education and the workforce is sometimes attributed to successful efforts by cultural ideologies such as feminism that opened doors for their education. Other times, women’s dominance in education is credited to the idea that reading, writing, quiet and sedentary classrooms are just more conducive to how women learn.

What really struck me in my research for this essay, however, was data from the National Center for Education Statistics. Analyzing college enrollment, from full-time and part-time to two- and four-year colleges, it’s clear that male enrollment stagnated after 1975. Female enrollment, on the other hand, began to increase in the college system at the two-year and part-time levels, often while they continued to work in the home, raise kids and care for extended families.

Late Baby Boomers and early Gen X women started making enrollment gains in part-time attendance and two-year colleges. In 1975, men outnumbered women in part-time fall enrollment by 84,295. In 1980, women took the lead by 566,671. When it came to two-year colleges, men were up by 361,482 in 1975. By 1980, women were up by 431,813 enrollments.

Women had slower gains in four-year institutions, but it’s the same trend that starts just after 1975. Male fall enrollment in four-year institutions in 1975 was 473,073 higher than female enrollment. By 1980, female fall enrollment was 42,888 higher, and by 1990 they were up by 425,043.

Whatever transpired between 1975 and 1980 – a myriad of social and economic changes for sure – that’s when men didn’t just start to fall behind. They actually stopped making gains in a very short timeframe.

From 1975 to 1992, the year I earned my master’s degree, men had increased fall enrollment at four-year institutions by only 76,269. In that same period, women had increased enrollments by 1,025,353. Meanwhile, 34,589 fewer males had enrolled in all colleges full time, while 1,110,635 more women did.

It seems to me that once the cultural and economic barriers lifted (slightly) for women, they started working hard and began to break out of the shackles of that oppression. Nothing in the educational system changed overnight that suddenly made it more conducive to women and less so for men. They were simply given a chance to work and they took it.

What happened to men?

I can only take wild guesses about these male trends since 1975. However, books such as “Of Boys and Men: Why the Modern Male is Struggling, Why it Matters, and What to Do About It” and “The War Against Boys: How Misguided Policies are Harming Our Young Men” offer valuable insights into these changes and their implications.

In “The War Against Boys,” Christina Hoff Sommers writes that “… it became fashionable to pathologize the behavior of millions of healthy male children. … No one denies that boys’ aggressive tendencies must be mitigated and channeled toward constructive ends. Boys need (and crave) discipline, respect, and moral guidance. Boys need love and tolerant understanding. But being a boy is not a social disease.”

In 2013, MIT economics professor David Autor wrote in his study titled Wayward Sons: The Emerging Gender Gap in Labor Markets and Education:

“Over the last three decades, the labor market trajectories of males in the U.S. have turned downward along four dimensions: skills acquisition; employment rates; occupational stature; and real wages. … Of equal concern are the implications that diminished male labor market opportunities hold for the well-being of others – children and potential mates in particular.”

On a personal level, I was culturally and economically predisposed to join the ranks of males lagging behind. However, as I drifted through elementary, junior high and most of high school, something else was forming in my mind: rebellion.

By junior high and early high school, I had become a fearless rebel without a cause. I taped Playboy centerfolds to the windows of my junior high principal’s office, threw rocks at cars and people, started drinking and smoking cigarettes, smarted off in class and fought boys in upper classes. Once, I had two fights at one kegger: “Won” the first one, with only one eye completely swollen shut by a punch, because the other kid gave up; and then lost the second after being repeatedly kicked in the head and losing consciousness. I also worked ranch and farm jobs, construction and at restaurants to make my own money.

While it felt like I was just having fun, I was also becoming aware of my reputation for trouble and the increasingly harsh consequences that comes with that reputation. I began to understand that like other (often years older) men I knew with similar reputations, I was heading for serious trouble or injury. Though I didn’t have the language for it then, desperation and hopelessness began to set in. I was on a one-way road to nowhere good.

But in my senior year, I read that novel, met the girl who has now been my partner for more than 40 years and made male friends who introduced me to punk rock and wild, nonviolent escapades with bikes, trampolines, junk cars and unhinged conversations.

Before I get into the specifics of that novel and the door it opened in my mind, I think it’s important to provide some early context for my rebellious attitude.

Boys are dangerous animals?

In rural Montana, before my family was flooded out of our small subsistence farm and moved to a nearby working-class suburb of Billings, no one talked to me about being a man or the traits of masculinity.

On the farm, on ranches and construction sites that I worked on from an early age, I was surrounded by men who embodied many cliched blue-collar traits, good and bad.

My father was among them. A professional country music musician, a trucker and operator of heavy equipment, he was also a drinker and a fighter. He espoused racist views that made no sense to me, since I’d only ever been around white people and some of them were crooks and dangerous men who’d spent time in prison. He was also the one man I spent much of my young life with – under trucks, tending farm animals and riding around in pickups. I drank with him or around him in my late teens. I spent endless hours with him as he worked and drank with other men. I often witnessed the raw violence he could exude through his eyes when challenged or suspected deceit.

My father also had a mind for wonders and his own deep skepticism of authority. Crawling on the gravel and dirt under trucks or working in barns surrounded by cows, horses and other farm animals, he’d say, “Believe nothing of what you hear and only half of what you see.”

I stood by helpless as he tied one of our more troublesome horses to the bumper of his car and dragged it into a trailer. I listened fearfully from my shared bedroom as he drunkenly held cats at arm’s length and shot them with a pistol. One night, I watched as he fired a .357 caliber handgun at a sister’s older boyfriend who was escaping in a car up the two-track country road from our farm. I cowered with sisters under a window in a bedroom when that boyfriend repaid the favor by firing an AR-15 he brought back from Vietnam at our house from a sandstone bluff.

After weeks of being attacked by a Rhode Island Red rooster, violently enough to draw blood from my 8-year-old back, my father locked me in a barn with the red demon. I had a large stick. The rooster, his virulence. I knocked him out of the air and would have killed him, but my father grabbed the stick out of my hands yelling “Don’t kill him!” Not every battle is a fight to the death, he seemed to be telling me. He liked and respected that rooster and called me “Rooster” after that fight.

My mother did her dead-level best to encourage respectable behavior in me, and my father did belt-whip the heck out of us from time to time – more out of reactionary fury than a strong sense of Biblical justice. We were not a religious family, after all.

And no, I didn’t cry much. Suppressing tears had nothing to do with being “manly.” Emotions of any kind were not a luxury I could afford. I learned early not to cry in front of my siblings; one of them would have told me to stop crying or she would give me something to cry about. It’s an old joke and they didn’t always mean it, but they meant it enough to be effective.

As for my elementary teachers in rural Montana, they were probably not as terrible as I remember them, but they did slap me, beat me with wooden paddles or rulers and try to shame me. One tied my hands behind my back and made me stand on the sidewalk during every recess for a week – for stealing a pencil from a classmate. Another hit me on the head with a stack of books when I said I’d never had anything displayed in the county fair. Growling through gritted teeth, she yelled, “That’s because you never try!” Wham! Several teachers lifted me off my feet by my ears.

In my memories, those 1970s rural classrooms were run by deranged, vindictive and violent old women. I refused to give them the satisfaction of crying. I was not afraid of them, nor did I care when they tossed me out into the hall for the rest of the day. I have wondered what difference it might have made if any one of them had instead given me a tape measure, pencils and paper and sent me out to measure everything in the playground instead of treating me like a dangerous animal.

I’m sure I “deserved” some of that treatment. School was a break from work on the farm and trucks, and I just wanted to laugh and run wild. The one thing I learned for those experiences was that anyone with authority was a threat.

Rebellion opened doors

As I noted above, the economy was in the tank in the early 1980s, and my father didn’t have his own jobs for me to work on the summer I turned 17. So, I got to play baseball for the first time that summer. I still worked in restaurants at night. As my senior year approached, he won a construction contract and wanted me to delay going back to school in order to work for him.

I don’t know how I knew, but I knew I would never go back to school if I didn’t return at the beginning of the year. My father, an independent businessman with an eighth-grade education, didn’t see the need for formal education. But by the time my senior year rolled around, I felt I had already lived the life of a construction worker and wanted … I didn’t know what, but something else, something more.

I yearned for a change from the monotonous life I was trapped in. The endless days of hard labor – milking cows, carrying water from the creek, feeding animals, nights spent washing and fixing trucks and loaders. The heavy drinking and violence. The running from cops, barely escaping arrest. The aimlessness. The powerlessness. I would watch planes fly high overhead, not knowing how or why you got on one and wondering if I ever could.

All of it had become oppressive, a grind.

So, I defied my father and went back to school. Later that year, I moved out of my family home. While I worked with my father and spent plenty of time with him over the following decade, I never lived “at home” again.

That’s the situation I was in when I met Mark, the book peddler.

I had noticed that the social studies teacher interacted with Mark in a respectful manner. The teacher, one of the few male teachers I’d ever had, seemed to genuinely engage with Mark’s thoughts and questions. Mark, skinny and studious, appeared more rebellious to me than the rest of us engaging in roughhousing, guffaws, flirting and being drunk or stoned or both, giggling at the back of the room.

I believe I spoke with Mark a few times after class, though I don’t remember what about. Then one day he handed me his copy of the science fiction novel “Orphans of the Sky” by Robert Heinlein.

I’m not sure how long it took me to open the cover, but once I did, I read it straight through several times. While I didn’t know many of the words Heinlein used, the story captivated my mind.

Briefly, “Orphans” tells the story of a young man who discovers through adventure and reading “secret” text that his entire world is inside a spaceship, a “generation starship.” No one in the story knew they were on a ship. The fact of their reality was hidden from them by time, myth and lies. Only when he encounters the freaks of that world, the mutants, the readers of forbidden books and thinkers, does he understand that there is an entire universe outside of the world he was trapped in. Beyond the sword-fighting and running adventure, it was language – words and facts – that had set him free. Books and words illuminated the way out of the life built for him and everyone else in his world.

After reading that novel, I began to study and interact in class. I formed friendships with young men and women who engaged in thoughtful and lively debates about anything and everything. Later that year, I participated in a week-long event for high schoolers on a college campus, which before then might as well have been an alien world on television. I figured out how to get student loans and Pell Grants. I figured out how to get into the community college in Billings and then the University of Montana, where I eventually earned an MFA in creative writing.

I still partied plenty and worked construction during summer breaks over the next decade and in bike shops during the school year. I learned how to read more than simple stories. I wore out a few dictionaries. I got an F on every one of my first-year college essays, but I stuck with it and learned from my failures.

I started to understand that I had grown up in a socially constructed world and economy that had constricted my parents as much as myself, much like the society in “Orphans of the Sky.” I believe that novel resinated with me so intensely because it showed me that I was in a made-up world and there was a constructive rather than self-destruct way to escape it. A lesson that has led me on a life-long adventure of seeking and publishing what truths I can find.

I’m relieved we’re paying attention to struggles that boys and young men are going through in our culture. I appreciate feminists trying to help young men recognize and overcome the brutality of toxic masculinity. I appreciate the men and women trying to help boys use their masculinity for good in the world. I appreciate my mother teaching me that boys have to be responsible in relationships. I appreciate my father, now dead, for demonstrating the value of hard work and showing me that sometimes you have to fight to defend your right to be in this world.

I hope that as we focus on boys, we don’t impose our expectations on them as if they are blank slates or beat them down as if they are dangerous animals. Instead, I hope we give them the time and space to be rebellious boys and build themselves up with the tools of knowledge. It’s a lot of trouble to let boys be boys, but I believe in us.